Okenekene Headdress

February 12, 2017 3 Comments

I came across the Okenekene headdress complex in December of 2016, while doing some research on a purchased piece (note: research post purchase) from the Merton D. Simpson collection. As indicated in a prior blog, I do have a weakness for the water spirit headdress.

The headdress is peculiar to Ijebu-Yorubaland[1] which occupies the costal plain between the interior Yoruba kingdoms of Ife, Ijesha, Egba, Ibadan, and Oyo and the coastal waterways. The Ijebu recognize the presence and power of spirits controlling Delta waters, and acknowledge that they adopted and adapted their Agbo masquerades from Niger Delta peoples (primarily the Ijo).

Here are a few examples,

Okenekene Headdress : The house and clock reflect the impressive quarters of the water spirits living below the surface. The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

The piece typically consists of three sections,

Back:

Typically shows coiled vines, and a heart shaped paddle, (or woro leaf). This will also have a chameleon, and or a python component.

Middle:

The middle area shows the abstract anthropomorphic representation of the water spirit with long pointed ears. Atop the domed area there may be shown an animal representation, or a more human related reference (e.g. an umbrella or rudder).

Front:

Typically reflects a reference to static/dynamic, natural/spiritual activity in the water.

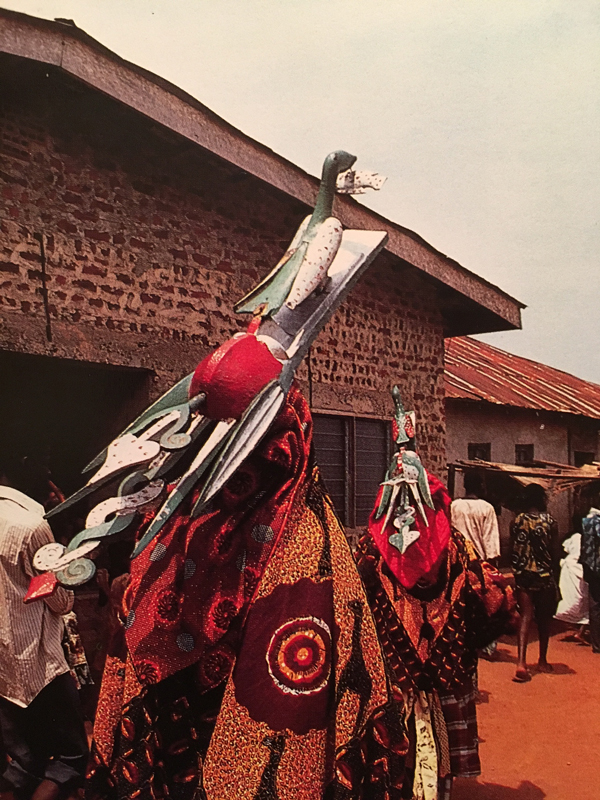

Okenekene : Showing chameleon, and python components at the back, the umbrella in the middle, and the fishing eagle within the waves to the front. [E1]

Okenekene : worn horizontally, they can be described as a juxtaposition of natural, spiritual, and human references. [E2]

Okenekene imagery in masquerade (1982): Ways of the Rivers, pg. 209.

Ijebu-Yoruba complex Components

Python[2]

Beliefs held by the Ijaw are of particular interest because these people are probably the oldest inhabitants of Nigeria. The Ijaw think that pythons hold the spirits of the sons of Adumu, himself a python, and the chief of the water spirits. Women are forbidden to mention his name or to approach his temples. At times lights may be seen gleaming below the surface of the water which this python deity inhabits. On some occasions the lights rise to the tops of the palm trees. Serpents are carved on the statue of Adumu at Adum’ Ama on a small tributary of the Santa Barbara River. Here come all who aspire to act as diviners or prophetesses. Such a priestess is forbidden to have relationships with a man; her husband is one of the sacred serpents. Every eighth day the water spirit is supposed to rise out of the water in order to visit his wife. On that day she sleeps alone, does not leave the house after dark, and pours libations before the Owe (water spirit) symbols. Inside her shrine are posts and staves representing serpents whose coils are said to typify the whirling dance performed in honor of the chief python god Adumu. “It is the spirit of the python that enters the priestess, making her gyrate in the mystic dance and utter oracles.”

When inspired, she will dance for a period varying from three to five days, during which she may not drink water. The language spoken during trance is said to be incomprehensible to the worshipers. In the Brass country, where Ogidia, the python war god, is worshiped, there are three main festivals in his honor. At the first of these (Buruolali), there is a presentation of yams at night, by a woman. These yams, which have been procured by the priests and chiefs, have to be in the form of serpents. At a second ceremony, a smooth-skinned male is offered as a sacrifice (Indiolali ceremony). Thirdly, there is Iseniolali. At this rite, women who have been appointed by the chiefs and priests gather shellfish. These are cooked at the shrine of Ogidia amid great rejoicing. Among the Ijaw people, pythons are never killed because they are thought to bring a blessing on any house they enter. At death the reptiles are buried with the honors of a chief.

Birds[3]

Birds also appear frequently in water spirit headdresses. For the Kalabari Ijo, these are probably references to oru ogolo, the talkative bulbul bird that is said to live in villages and to speak the language of the spirits. It communicates messages from the spirits to the humans.

In Agbo masks, birds ride on the backs of crocodiles and on the snouts of such masks as Igodo and Okenekene. In these latter instances the bird is probably a fishing eagle.

For the Ijebu, the bird is linked with water spirits, as it is in the Delta.

[1] Ways of the Rivers, pg. 197

[2] The Serpent in African Belief and Custom, WILFRID D. HAMBLY

[3] Ways of the Rivers, Martha G. Anderson & Philip M. Peek

[E1] Ways of the Rivers, pg. 203

[E2] Africa – Dictionaries of Civilization, pg.197