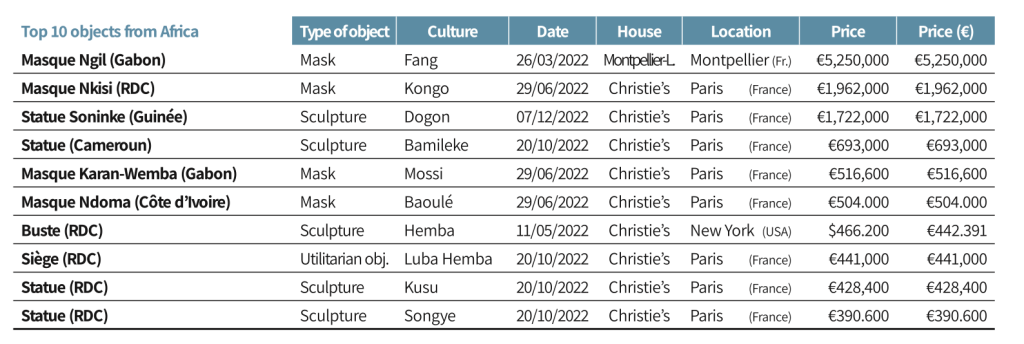

Collecting African Tribal Art : Ten top items sold in 2022

October 7, 2023 Leave a comment

The following ten African items (by sales price) as reported by Artkhade :

1. Nigil Mask (Gabon)

The sale of the mask follows an insane twist :

An elderly couple in France has accused an antiques dealer of cheating them out of a seven-figure payout after learning that the African mask they sold him made €4.2 million ($4.4 million) at auction. According to Le Monde, which first reported the news, the unnamed couple has launched a lawsuit against the dealer, asking an appeals court in Nimes to determine what compensation is owed them.

The mask was discovered while the pair cleaned out their property in preparation for a garage sale. The mask, however, was put aside for the local antiques dealer, who agreed to buy it for €150 (about $157) in September 2021. Months later they read in the newspaper that the mask had been sold for millions at an auction house in Montpellier. Per the listing, it was a traditional Fang mask from Gabon used in weddings, funerals, and other rituals. The mask—a rare sight outside of Gabon, with less than a dozen held in museums worldwide—was brought to France by the husband’s grandfather, who was a colonial governor in Africa. [source]

2. Nikisi Statuary (RDC)

RÉPUBLIQUE DÉMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO

Price realised EUR 1,962,000

Estimate EUR 1,000,000 – EUR 1,500,000 [Christie’s]

Lot Essay segment [Christie’s]

“Nkisi N’Kondi – hunting spirit. An object of magic and ritual, and due to its size, certainly belonging to the community or even to a lineage or clan, it was intended to be feared. Linked to the nganga, the only one authorized to handle it during consultations, this pairing made it possible to grant wishes, protect and conjure up spells at the request of the consultants. The serendipity of metal objects implanted in the fetish remains a physical and concrete signature of the repeated and prolonged use it had within a Kongo community. The ventral cavity, sealed with a large crusty aggregate, called the magic charge, indicates the importance and strength with which the nganga and the spirit engaged in the earthly world. The fetish becomes omnipotent in this way, as a true transcendent power, in an elusive vital breath that is actually ingrained.”

3. Soninke Statuary (Mali)

Price realised EUR 1,722,000

Estimate EUR 700,000 – EUR 1,000,000

Lot Essay segment [Christie’s]

“Initially associated with the corpus of Dogon statuary, then referred to as proto-Dogon, it can now be linked to the Soninke diaspora which, in successive waves between the 9th and 13th centuries, migrated from the empire of Ghana to the Mandé region and then to the cultural and economic center of Djenné-Jeno6. It finally found refuge around the 13th century in the west of the Bandiagara plateau, thus preceding the Dogon populations who were inspired by their iconography. Based on the work of Dieterlen and Zahan, de Grunne associates the corpus in question more precisely with the Kagoro, a Soninke clan whose oral tradition maintains that they fled the Mandé kingdom because of dynastic quarrels and the growing influence of Islam at the court of the emperor of Mali in the 12th and 13th centuries. Both de Grunne and Leloup have also demonstrated the plastic similarities between Soninke wood carvings and the production of terracotta and metal works from the Inner Niger Delta. These similarities led Leloup to name this corpus Djennenké.” [Christie’s]

4. Bamileke Statuary (Cameroon)

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“It is not uncommon among the Bamileke for great servants to be elevated to the supreme rank of wambo at the end of their career, which places them almost at the same level as the king. Such a social ascension confers on them the privilege of owning a portrait, which is otherwise reserved only for the king. Produced exceptionally, and after special authorisation from the fon, as a recognition for notable merits, these effigies convey the importance of social status to the highest degree. In this sense, it is not uncommon to see the notable represented with nobilary symbols such as cups or pipes.” [Christie’s]

5. Karan-Wemba Mask (Mossi – Burkina Faso)

BURKINA FASO

Price realised EUR 516,600

Estimate EUR 200,000 – EUR 300,000 [Christie’s]

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“Within the rich repertoire of Mossi masks, the karan-wemba type is among the rarest and most important. Typical of the Yatenga region, these masks stand out for their flamboyant aesthetics, similar to the n’domo masks of the Bamana or the satimbe produced by their Dogon neighbors. Like the latter, they evoke the founding figure of a clan’s woman-ancestor. It is through these masks that we discover the original conceptualization of a feminine ideal, illustrated in both a political and aesthetic dimension. The karan-wemba masks fascinate in particular because of this successful functional and formal synthesis. To paraphrase Leo Frobenius, “it is only when one has succeeded in observing the emergence of the conceptions and customs that have [created] these masks that one can consider that the forms of the latter have become intelligible.” Here, ancestral primacy and plastic abstraction are but two aspects of the same concept.” [Christie’s]

6. Ndoma Mask (Côte d’Ivoire)

Price realised EUR 504,000

Estimate EUR 500,000 – EUR 600,000 [Christie’s]

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“Ndoma, which could be translated as “double”, is one of the manifestations of the dualism that characterizes this large group (Baule), occupying the centre of the Ivorian hinterland, where nothing is clearly established. Everything is bivalence and uncertainty in a world divided between the order and protection offered by the village and the threat of the encircling bush, the reign of dangerous species and spirits that are often malicious. Since beauty has no gender, one might wonder about the gender of the portrait described in these lines. The presence of a crenelated ornament bordering the cheeks and chin, although it intuitively evokes a beard, should not mislead us: although the dancer who wore this type of mask during joyful mblo celebrations, commemorations or mourning, was a man, we are nonetheless inclined to see in it the image of a woman, as testimonies from various periods encourage us to do, according to which it was mainly to the lady of his thoughts that this homage was intended. In the Akue locality of Kami, the “village of masks” as an observer from the beginning of the 20th century called it, Susan Vogel, in the 1970s, was able to photograph a mask and its model, an elderly village woman who revealed to her the time and conditions in which an artist had immortalized her features. Sculpted in 1913 by Owie Kimoh, this object was also adorned with the same kind of beard-shaped ornament, thus following a stylistic tradition whose oldest known representative enriched Marceau Rivière’s collection for a long time.” [Christie’s]

7. Hemba Statuary (RDC)

Price realised USD 466,200

Estimate USD 300,000 – USD 500,000 [Christie’s]

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“Lusingiti figures commemorate ancestors and carry strong genealogical symbols. These powerful figures are known to reinforce kinship ties as well as to encourage solidarity and harmony amidst individuals. Their carving takes into account a canon of well-established symbols and iconographic details. For instance, the position of the hands resting on the navel refers to the protection and goodwill ancestors extend to all members of a lineage.

While these ancestor figures are for the most part masculine, they bear witness to the fact that the catch-all term Hemba refers to a politically decentralized entity. This decentralization is evident in the various hairdos – a prerogative of the ruling class – which is a compositional element that often reaches a high degree of complexity. Thus, they link a given object with a specific Hemba ancestor. It is possible to reconstruct, through the help of these figures, the corresponding territorial interrelations and lineages. Owning such a figure means that the chief of a given clan is fully entitled to political leadership.

Based on François Neyt’s analysis, lusitigi figures belong to twelve different groups. This daring classification represents a useful ‘grammar’ which helps in understanding the entire body of work. Several common denominators have been identified by Neyt namely the careful carving of the legs, the shape of the face and the finely sculpted geometry of the coiffure as well as the sensuality of the umbilical region.

According to Neyt’s theory, the sculpture of this lot may be classified as belonging to the ‘classical Niembo style’. This style shows a great sense of elegance and it is here expressed by the powerful serenity of the gaze, the intricacy of compositional elements and the geometric beauty of the hairdo. By merging naturalism to the hieratic aspect of the icon, the object emanates with a sense of surreal majesty which is further enhanced by the ‘bust-like’ appearance of the artefact as it has come down to us.

This sculpture is closely related to several pieces described in Neyt, F., La grande statuaire Hemba du Zaïre, Louvain-la-Neuve, 1977, pp. 65-71, fig. I. no. 3, 5, and 6.” [Christie’s]

8. Caryatid Stool (RDC)

RÉPUBLIQUE DÉMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO

Price realised EUR 441,000

Estimate EUR 500,000 – EUR 700,000

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“The monoxyle wooden seats supported by a figure in the round – most often female – are a recurring motif in African statuary and are among its most original creations. At the beginning of the 20th century, when they were freed from the ethnographic sphere to be also consecrated by the circles of the avant-garde and then by the art market – where “the most mysterious relationships” were established – they became caryatids. This term, borrowed from ancient architecture, anchored these chairs in the anthology of Art History and established them as the new classic.

As soon as African art was “discovered” in 1906, artists began to create variations on the caryatid – inspired by works that were clearly African, not Greco-Roman. Several authors, including Schneckenburger (Welt Kulturen und moderne Kunst, 1972), have in particular compared the caryatids designed by Modigliani with Luba seats. These plastic affinities have also been noted in Lipchitz’s work: “In a widespread type of Luba sculpture, a figure supports a chief’s seat with her arms raised at her sides like those of Lipchitz’s figure, [Mère et Enfants]” (Stott, D., Jacques Lipchitz and Cubism, New York, 1978, p. 109). William Rubin, on the other hand, detects them in Picasso’s caryatid sketches, offering the “same iconic and frontal character, and a similar pattern of symmetrical forearms raised vertically” (Rubin, W., Primitivisme dans l’art du 20e siècle, Paris, 1987, p. 288). In these avant-garde caryatids, the proportions and the stylisation of features reveal above all the architectural intelligence that European artists envied in African art.

Indeed, these caryatid chairs are unique to the history of African art. They visually embody the sacred aspect of power – as anchored in the creative myths of the Dogon, or drawing on the dynastic lines of the kingdoms from the Cameroonian Grassland. In the Southeastern region of the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo, these metaphors of royal power all stem from the same origin – that of the powerful Luba kingdoms – and from the same essence, placing women at the source of spiritual power and in equal measure within the political system. The opulence of the body ornaments – scarification and hairstyles – identified these female figures as members of prestigious families. “Thus represented, women acquired a symbolic value as “pillars of the state” (Homberger, L., Sièges africains, Paris, 1994, p. 109).” [Christie’s]

9. Kusu Statuary (DRC)

Price realised EUR 428,400

Estimate EUR 250,000 – EUR 350,000 [Christie’s]

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“When her collection of African art was dispersed in 1977, Charles Ratton appraised this statue as Luba. Ten years later Alain de Monbrison introduced it under the Kusu ethonym. Finally, in 2004, François Neyt, while confirming its attribution to a Kusu artist, brought it into the Songye area of influence.

In contrast to the infatuation with autonomous and hermetic styles that has long prevailed in the study of African art, this effigy of an ancestor brilliantly personifies the dynamic of the inter-cultural relations of the south-eastern region of the current Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the intersection of the Luba, Songye and Hemba countries, this dynamic sometimes results in occasional borrowing, such as in the interpretation of a Luba headrest by the Songye Master of Kananga (Pavillon des Sessions, Louvre Museum, inv. no. 73.1986.1.3). Meanwhile, other corpuses reflect more lasting influences, rooted at the very core of a sculptural tradition and part of its history.

The essence and individuality of Kusu statuary comes from the complex migratory history of the Kusu people, spread across these three powerful countries, and then from the dispersal of their tribes throughout a vast region between the Songye and Hemba territories, which is between the lower Lomami River and the western bank of the Congo River (Neyt, F., La grande statuaire Hemba du Zaïre, Louvain-la-Neuve, 1977, p. 271). Kusu effigies paying homage to both legendary ancestors and mythical heroes stem from Luba-Hemba cultural identity, and their magical-religious statues stem from Songye beliefs (Felix, M., 100 peoples of Zaïre and their sculpture, Brussels, 1987, p. 66).” [Christie’s]

10. Songye Statuary (RDC)

RÉPUBLIQUE DÉMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO

Price realised EUR 390,600

Estimate EUR 400,000 – EUR 600,000 [Christie’s]

Lot segment [Christie’s]

“‘Unique in its genre’ (Neyt, idem, p. 321), simply by the monumentality of its stature and its features, it embodies the aesthetic of the strength expressed by the statuary of the Songye Tempa people. Out of the proliferation of added elements (feathers, animal skins, vegetable fibres, copper leaves) typical of this corpus and visible signs of the ancestral alliance of the sculptor, the blacksmith and the divine priest (nganga), all that remains is a fragment of the horn stuck on the top of the head. What stands out, therefore, is the genius of the master sculptor.

It is in the roundness of the shapes and the austere tension of their curves that the artist has gifted Songye statuary with one of its most powerful interpretations. Highly individual, this effigy is the artistic representation of the metamorphosis of the ancestor into an unshakeable protector of the balance of the community. The necessary mobilisation of protective powers is represented by the classic position: standing, with the hands framing the abdomen, and is accentuated by the effectiveness of the short torso, focusing the eyes on the bevelled hands, whose fingers stretch out to brush against the navel. Echoing the broadness of the shoulders, the powerful scansion provided by bulges in the neck (a reminder of layers of snakeskin necklaces) enunciate the monumental impact of the head.

The huge mouth stands out from the head in a lying-down figure of eight. This intensification of one of the archetypal traits of Songye Tempa statuary highlights the imposing simplicity of the oval face, contained by the minute raised, clean single outline of the headdress and ears, and in the strength of the cowrie shell eyes, whose brightness contrasts sharply with the darks shade of the patina. ” [Christie’s]