Collecting African Tribal Art : Spiritual Energy of African Tribal Art

February 12, 2024 Leave a comment

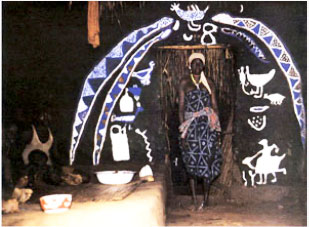

Plants typically absorb sunlight and convert the energy through photosynthesis to usable chemical energy while releasing oxygen. Humans convert food into chemical energy to support physical processes in the body. The physical process is part of an entire interconnected and balanced ecosystem. Beyond this however the human species possesses the faculty to create, comprehend and develop logic. This abstraction is the module within which the ‘African Tribal Spirit’ has been isolated and developed into a potent source of motivation, moderation, projection, control and self development. The purpose of the African Tribal Art in the ‘religious or protective’ (versus utilitarian) sense is to stimulate conditioned mechanisms via either an individual or on a collective basis, within the larger framework of a village or community.

Let’s take a look at a couple examples.

Wheelock Cat #139

This mask is attributed to the Bwa in Boni and Dossi. It represents “the butterflies that metamorphose and rise in clouds around the pools of water left by the first rains of spring. These masses of butterflies are a manifestation of the power of new life and the awesome power of the blessings of ‘God’…. This particular style [referring to a straight protuberance versus a hooked beak] , very long and decorated with a linear series of nested circles, is the only style correctly spoken of as a ‘butterfly’ or, more accurately, a spirit that takes this butterfly form.” The use of this mask in a ritual masquerade reinforces common ideals of beauty and respect for the environment held by the community. It may also play a part in developing the framework of a benevolent God-figure. On an individual level it may also act as a trigger in remembering an occasion where one may have witnessed a rabble of butterflies. This process is the ‘African Tribal Spirit’ – the mask itself while treasured and appreciated is not necessarily deified.

Buffalo Helmets [Constantine Petrides]

The article (see link above) says “As a result of the animal’s cultural connotations, buffalo imagery is prevalent in the arts of many sub-Saharan cultures. Its behavior and anatomy have served as a special source of inspiration in many of the subcontinent’s masquerades. In Central Africa, in addition to the realistically rendered depictions of buffalo heads in the helmets of Tabwa people, one finds a large number of carved buffalo heads especially among the so-called Kwango cultural complex in southwestern Congo – including Yaka, Sulu, Pende, and Holo (see Bourgeois 1991).”

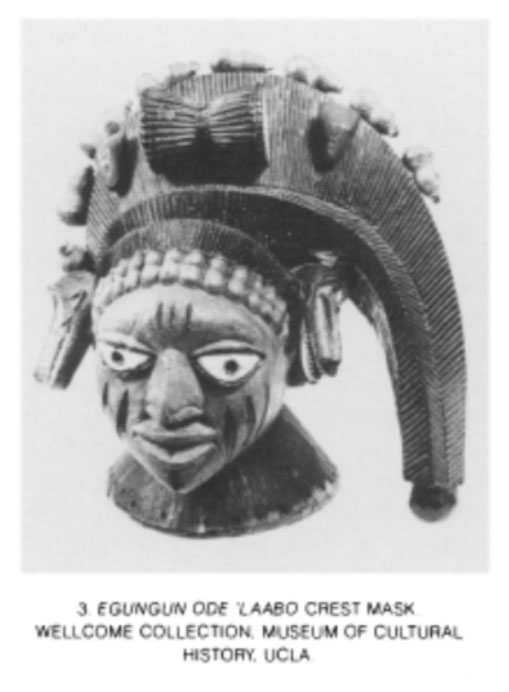

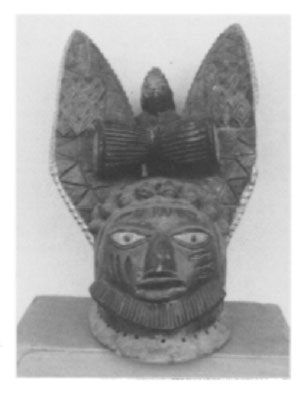

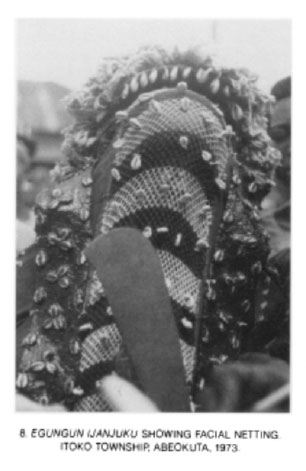

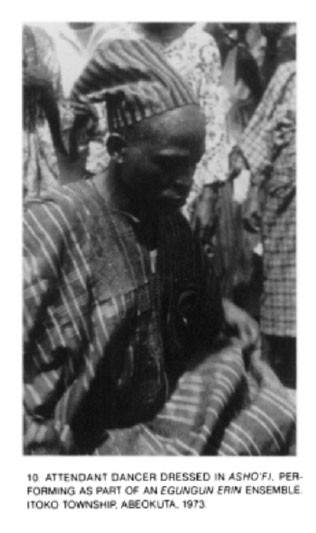

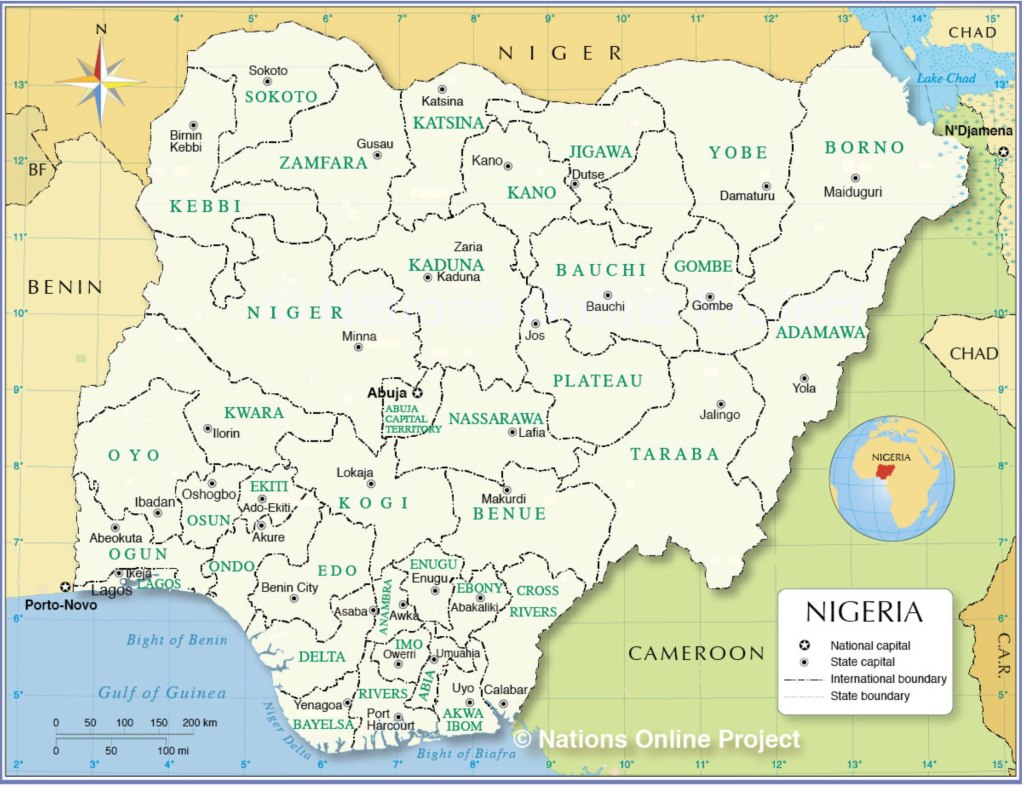

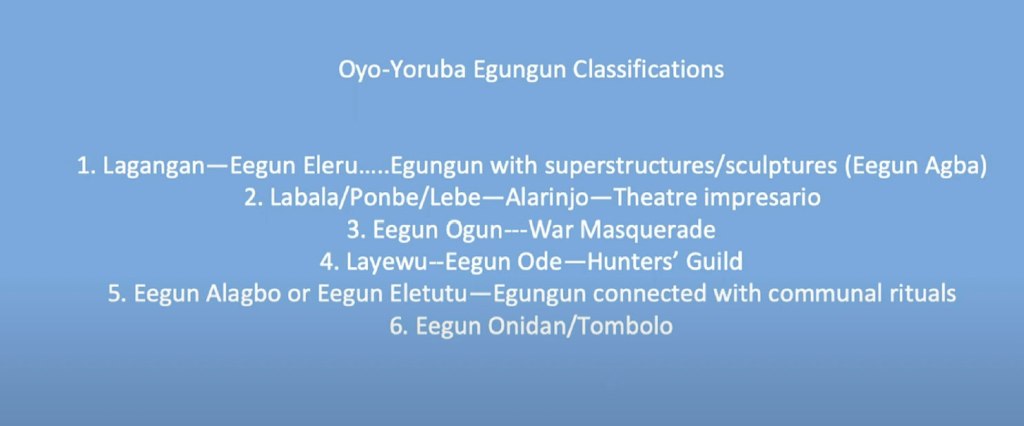

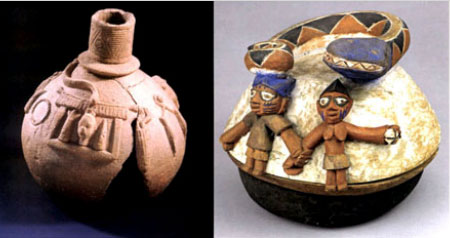

The Spiritual energy of African Tribal art is not limited to the imagery of animals but can also be established via behaviors, ideals (discipline, bravery, moderation of aggression) and the intangible framework of a specified cosmological framework, eg. Ikenga, and Egungun from the Igbo and Yoruba peoples respectively.