Collecting African Tribal Art : Ikenga as Philosophy and Form

April 8, 2024 Leave a comment

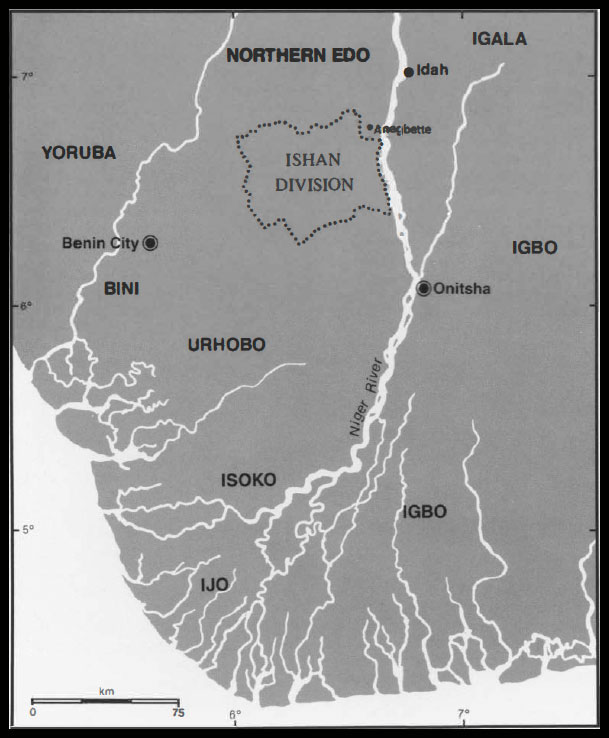

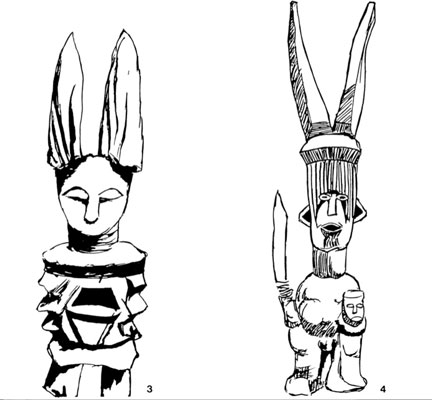

This blogpost is a response to a reader who wanted clarification on the role of the head held in the left hand of ikenga statuary. Physically it represents the decapitated head of the victim or enemy. It may in a way symbolically represent the achievement of the goal within a framework based on recognized societal achievement and success. There are ikenga which carry symbols of “elevated rank” which again is in keeping with the philosophy of “goal achievement”. There are also ikenga which carry defensive weapons (eg. a shield) in the left hand which may carry a whole different connotation related to the need for constant preparedness, struggle and survival. What the following excerpts from the article “The Ishan Cult of the Hand [Lorenz, Carol Ann]” will demonstrate is that the philosophy and form of ikenga has spread to mean many things to many peoples including but not limited to Igbo, Igala, Ishan, Isoko, Urhobo, Ijo and Bini.

Igbo

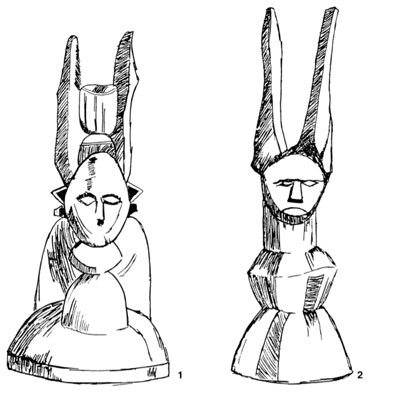

“It has often been suggested (e.g. Odita 1973; Boston 1977:2; Cole & Aniakor 1984:24) that the Igbo people are the originators of the cult of the hand, which they call ikenga or ikega. Widespread and highly developed, with numerous and varied images (Cole & Aniakor 1984:24), Igbo ikenga is a male cult that stresses the right hand and represents the force of a man’s individual strength, skill, industry, status, and wealth. A pair of horns, connoting masculine strength and aggression, is the most essential element in the carved image. Ikenga sculptures are differentiated in form, size, and degree of elaboration according to the achieved status of the owner. More elaborate examples are usually figural, commonly depicting a warrior carrying weapons or decapitated heads, or else symbols of elevated rank such as staffs of office, tusks, horns, and various ornaments.”

Igala

“The Igala version, called okega or okinga, can be found in two very limited geographical areas, in the southwestern lbaji district and in and around Idah (Boston 1977:87), both of which have had extensive contact with Igbo peoples. Some okegas are reminiscent of Igbo ikenga carvings in form and style, but in the Idah area, a unique okega form developed with two or more tiers and multiple figures of both men and women (Boston 1977:87, 89). The latter belong to hereditary lineage leaders and stress the “achievement of a whole clan and of all its members, both men and women” (Boston 1977:94) in contrast to the Igbo emphasis on individual masculine success and competition.”

Bini

“In Bini country, the cult of the hand, called ikegobo or sometimes ikega (Bradbury 1961:133), is known primarily from the court of Benin, where kings and chiefs have venerated the hands as a personal spirit at least since the reign of Ewuare in the fifteenth century (Egharevba 1949:88-89). Like Igbo ikengas, Bini ikegobo sculptures exhibit a number of symbols of aggression: warriors fully armed for battle, weapons, beheaded corpses, severed heads, and predatory animals. There is also, however, an emphasis on status and wealth, including figures swathed in abundant lengths of cloth, with elaborate ornaments and hierarchically arranged attendants. The basic element of the Benin ikegobo is a representation of a “box-stool” (Vogel 1974:8), which serves as both a seat and a treasure container. This stool image, rather than horns as in Igboland, is the most important feature of the Benin ikegobo (Boston, cited in Bradbury 1%1:138, n. 14), which in fact lacks carved horns and instead often has a post, or a hole for an inserted stick, designed to support an actual tusk or horn. Other differences between Benin and Igbo practice, according to Bradbury (1961:133-34), are that Benin ikegobo are intended for the praise of both hands rather than just the right hand, and that a high-ranking or wealthy Benin woman might have an ikegobo of her own, although such instances are not common.”

Urhobo & Isoko

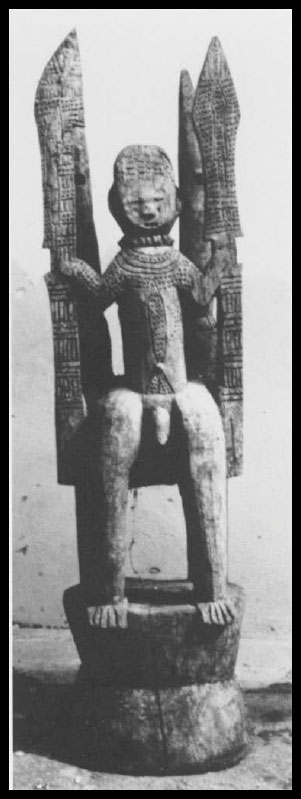

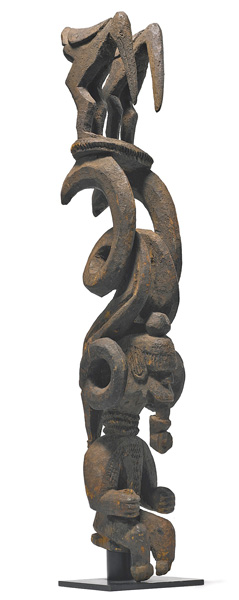

“The Urhobo (Vogel 1974:11) and Isoko (Peek 1981: 143; 1986:47) divide the twin values of the cult- status and wealth on one side, strength and aggression on the other – into two separate cults. The cult of the right hand is called obo, or “hand,” and is associated with a small and simple stool-like image that occasionally has an additional horn on top (Vogel 1974:11). A second cult, called ivri (spelled in a variety of ways), is concerned with determination, aggression, and warfare, but may also have a protective or antiaggression function. The ivri objects depict a massive beast with a huge belly, gaping mouth, and prominent teeth. A human figure representing the owner or his “spirit double” (Peek 1981:42) sits or stands above this creature, often flanked by smaller attendant figures; it has been suggested that this hierarchic arrangement reflects Benin’s stylistic influence (Foss 1975:141).”

Ijo

“An image like the ivri, called efiri or ejiri, may be found among the Western Ijo. They also have an object known as ikenga or amabra, consisting of a stool with a low-relief face on top, or a twohorned figure reminiscent of an Igbo ikenga (Horton, cited in Bradbury 1%1:138, n. 14). The efiri and amabra images seem to be of limited distribution in Ijoland, confined to areas most in contact with Igbo and Southern Edo cultures. As in Igboland, the ivri and efiri are normally restricted to male ownership (Peek 1980:59) and the size and elaboration of these figures depends upon the “power, wealth, and prestige of the owner and his ability to control the image once made” (Foss 1975:134-35). Furthermore, the owner figure often is depicted with attributes of the warrior, including feathered headdresses, weapons, and severed heads.”

Ishan

“Ishan ikegobo may take several different forms, some of them sculptural and others resembling ordinary domestic utensils. All are relatively small, ranging from about 7.5 cm. to perhaps 38 cm. in height, and simply formed and decorated. The commonest type is shaped like a small hand pestle (olumobo), which is similar in form to a stool.”

“Among the Ishan, the cult of the hand is called ikegobo or ikega as in Benin, but also by variant names including ikekobo, or simply obo (“hand”), as among the Southern Edo. It can be found in almost

every area of Ishan country, its absence today in the most northerly kingdoms seemingly attributable to the encroachments of Islam. Ishan ikegobo is one of a variety of religious practices designed to protect the individual and his family and to secure his fortune, warding off evil and bringing good luck. It is integrated with other forms of religious expression, most notably the veneration of ancestors. Often the senior male maintains his family’s ikegobo together with the paternal ancestral shrine; it seems that upon its owner’s death the ikegobo is never destroyed but is preserved instead as a relic of the deceased. As in Benin, the Ishan cult of the hand is one of the trio of personal cults including also the veneration of the head (uhomon) and of one’s personal guardian or destiny (ehi). Both Benin and Igala practices may have influenced the fact that in Ishan, the cult of the hand is less rigidly masculine in its orientation. Both the Igala and Ishan cults are also similar in that they downplay the concept of individuality of achievement, instead emphasizing familial or communal welfare.”

“Like the Southern Edo obo cult, the Ishan ikegobo stresses success, achievement, good luck, and the accumulation of wealth. One sacrifices to the hands in order to thank them for past successes and to petition them for future benefits. But unlike the Southern Edo version, there is no complementary cult comparable to ivri that focuses on aggression or protection from violence. Those concepts are simply absent from the Ishan ikegobo cult as it is practiced today, and there is no hint that it ever had such connotations. There are no warrior figures, no decapitated victims, no images of weaponry, no devouring beasts.”

“The Ishan cult of the hand is concerned, rather, with seniority. Usually only the elderly may establish a shrine to their hands. Although ownership of many Ishan art forms is the prerogative of high-ranking individuals, the ikegobo cult and its sculptures represent one aspect of the culture that is particularly nonelitist. Anyone of sufficient age may have an ikegobo carved, regardless of social position or profession. Moreover, since all are carved in wood, no distinctions are made on the basis of the type of materials. In fact, the ikegobo of a king may not be any larger or more elaborate than, or otherwise distinguishable from, those of his subjects.”