Collecting African Tribal Art : Djenne Beauty!!

March 30, 2024 Leave a comment

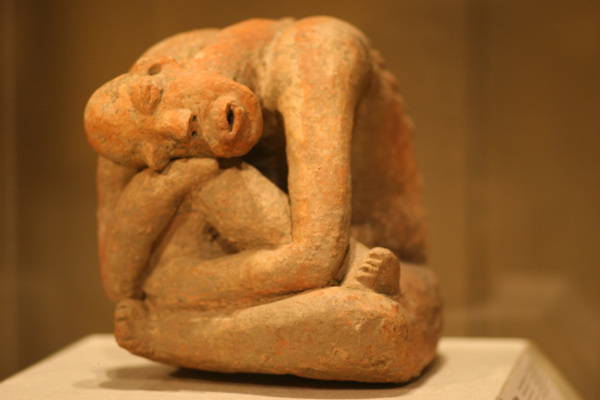

Achieving postures which seem realistic would seem fairly easy to do given the flexibility of prefired clay. However this is not typically the case. Djenne statuary is so impressive the sculptors were able to impose impossible positions on statuary without losing sinuous flow and still convey a high level of human depth of feeling and emotion.

In the photo/video link above the right leg seems to lend itself in a very natural overall composition, however on closer inspection it would have to be broken at the ankle to achieve this. Additionally the severity of the open wounds, the goiter and the size of the worms emanating from the body would not be possible. The distended abdomen and the thin arms also point to Kwashiorkor, a condition resulting from inadequate protein intake leading to loss of muscle mass and a large protuberant belly.

Paradoxically one can only marvel at the strength and perseverance displayed and empathize with the subject’s plight.

Excerpt from previous Blog post:

Consider a similar perspective form Bernard de Grunne on Djenne-Jeno,

“As to the meaning of snakes, VanDyke has found at least 200 figurative works with herpetological symbolism (Disease and Serpent Imagery in Figurative Terra Cotta Sculpture from the Inland Niger Delta, of Mali). She suggests that some of these snakes could represent parasitic worms coming out of the mouth, ears, nose and even vagina of some figures. I have also underlined the ancient symbolism attached to snakes starting with the founding myth of Dinga, the first king of the Soninke Wagadu empire circa A.D. 800, who fathered many children and one large snake called Wagadu Bida. Snakes, thus, are connected to ancestor worship but could also relate to the treatment of diseases represented in the seated figure analyzed here. In the ancient oral histories of the Wagadu and Mali empires, illness was framed as a spiritual test and overcoming it, a mark of spiritual power for both the afflicted and their healers. Such beliefs persist into the present.”

![[E2] Djenne-map](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/djenne-map.jpg)

![[E3] Djenne terracotta - Metropolitan Museum of Art](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/met-jenne-03.jpg)

![[E4] Djenne terracotta - Metropolitan Museum of Art](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/met-jenne-02.jpg)