These notes provide some historical perspective on the age of sub-saharan African terracotta, location of origin, cultural traditions, and pricing. While developing an African Tribal Art collection the main source for great older pieces are auctioned collections whose owners have developed their own specific sub-collections.

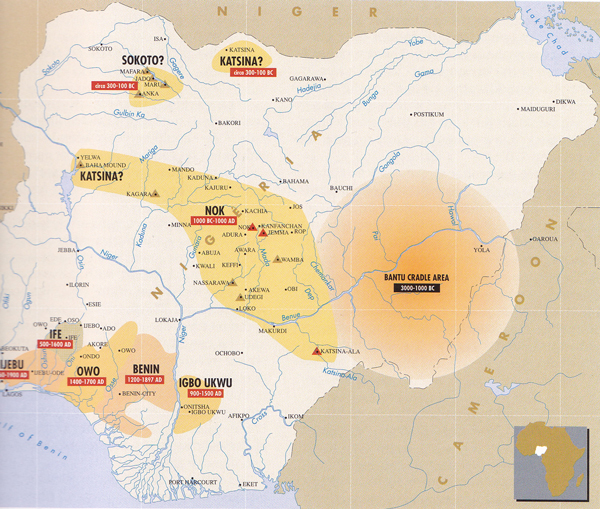

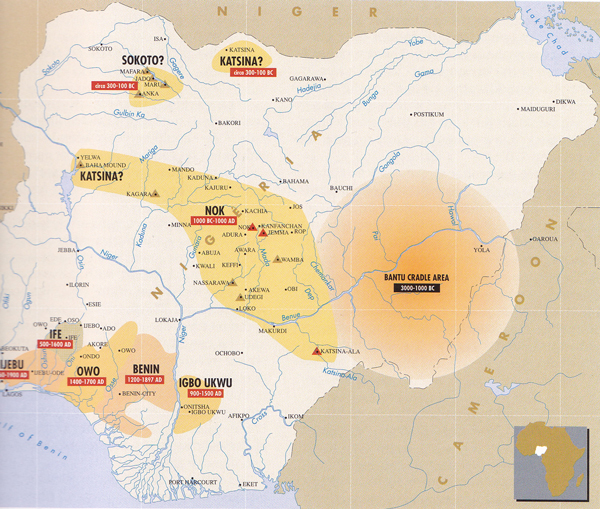

Map of the Ancient Civilizations of Nigeria

Source: Bernard de Grunne; The Birth of Art in Black Africa, 1998 pp.19.

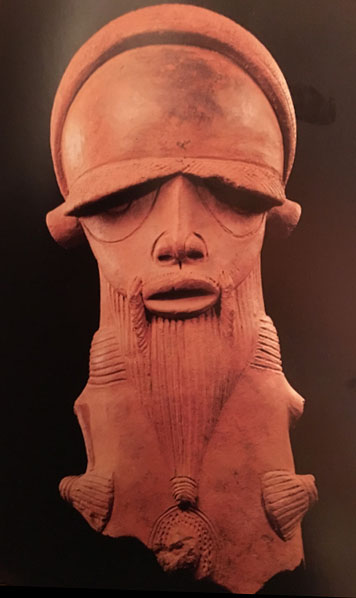

Nok head fragment.

Description : Jos Plateau region, Central Nigeria, West Africa, 500 BCE to 200 CE. Terracotta with heavy temper and remains of a finer burnished surface slip. 6-1/2″ H. Mounted on steel base. Classical Nok terracotta was first found in 1943 deep within a tin mine, near the present-day town of Nok, situated on the Jos Plateau in central Nigeria. The exact use of these portrait-like figures has yet to be discovered; none of these sculptures has ever been found in situ and any remains of ancient structures are practically non-existent today. However, it has been suggested the hollow terracotta figures, which this head came from, were ancestral effigies kept in shrine houses. This hollow terracotta example is made of a coarse, quartz-tempered clay. The features were hand-modeled and show a remarkable sophistication for such an early date in Iron Age, Sub-Saharan Africa. The style of Nok facial features shows similarity to more historic and contemporary bronze and wooden sculptures found among the Benin and Yoruba peoples of Nigeria. It has been said these ancient figures represent the beginnings of black African art.

Provenance: Eugene Behlen, once head of the dept. of exhibitions at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, for 25 years. Acquired prior to 1987.

Estimate: $3,00-$4,000

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2014

Djenne Sculpture

Female Figure with Four Children

12th–17th century

Terracotta

35 x 21.5 x 18.5 cm (13 3/4 x 8 7/16 x 7 5/16 in.)

Charles B. Benenson, B.A. 1933, Collection

2006.51.116

Geography:

Made in Inland Niger Delta, Sahel, Mali

Culture:

Djenne

Classification:

Sculpture

Status:

On view (2015)

Bibliography:

Warren M. Robbins and Nancy Ingram Nooter, African Art in American Collections (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989), 67, fig. 41.

Susan Vogel and Jerry L. Thompson, Closeup: Lessons in the Art of Seeing African Sculpture from an American Collection and the Horstmann Collection, exh. cat. (New York: The Center for African Art, 1990), 12829, fig. 55.

“Acquisitions, July 1, 2005June 30, 2006,” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin (2006): 222.

Art for Yale: Collecting for a New Century, exh. cat. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 2007), 178, pl. 162.

Frederick John Lamp, Accumulating Histories: African Art from the Charles B. Benenson Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Art Gallery, 2012), 66, 134, ill.

Bernard de Grunne, Djenné-Jeno: 1000 Years of Terracotta Statuary in Mali (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2014), fig. 12.

Photo credit: Yale University Art Gallery

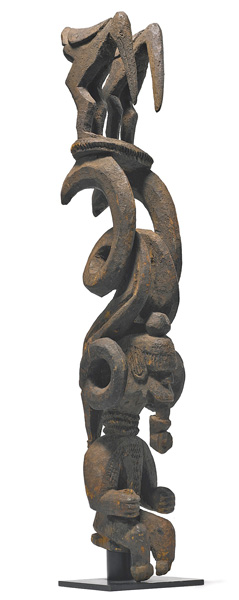

Dakakari sculpture

Description : Dakakari culture, Nigeria, ca. 19th to 20th century CE. This large, hollow pottery figure shows a four-legged, horned animal (maybe a hartebeest?) with ears erect and a collar of some kind around its neck; it stands perched atop a bulbous rough sphere. Pottery of this kind was observed in Dakakari graveyards through the 1940s, but it recalls that of the Sokoto (among others), the ancestors of the Dakakari who lived 2000 years ago in the same part of Nigeria. Ethnographic accounts say that some graves had up to fifteen pieces of pottery like this placed around them; these were frequently broken and a description from a Dakakari graveyard in 1944 by a visiting Englishman laments the scattered pottery around the area — but this destruction was certainly intentional. Dakakari women were the potters and passed their skills down via their daughters.

Size: 7.5″ W x 26″ H (19 cm x 66 cm).

Provenance: Ex. Peter Arnovick Collection

Estimate: $700-$800

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

Katsina Head

Description : Africa, Northeast Nigeria, Katsina, ca. 1st to 4th century CE. An ancient Katsina terracotta janus (double-headed) figure that once belonged to a statue that would have measured approximately 15 to 30 inches tall. Both sides of this piece depict a bearded male. Very few Katsina janus heads have been documented, according to scholar Claire Boullier. What’s more, the shared stylings of these heads demonstrates that they were actually created by a single sculptor which corroborates the progressive idea that Katsina sculptors possessed individualized styles almost 2000 years ago. This said, the sculptor still adhered to stylistic rules embraced by the Katsina culture such as the globular head form, the half-closed eyes, short nose, and pointed chin–all characteristics adhered to by most Katsina sculptors. Additional intriguing features include the perforated ear plugs, pronounced unibrow, parted lips with slightly jutting lower lip, and elaborately incised coiffure with two applied nodules over each forehead. The visages of this piece also show traits akin to Nok figural sculpture such as elongated heads, high smooth foreheads, and elaborate fanciful coiffures, as Katsina visual culture was most certainly influenced by the Classical Nok culture. Scholar Claire Boullier also points to similarities between Katsina and Sokoto sculptures that may prompt further exploration of the networks between these ancient African cultures. For discussions of a similar Katsina janus head see Claire Boullier, “African Terra Cottas. A Millinary Heritage, musee Barbier-Mueller and Somogy (eds), 2008: cat. 81 p. 190.

Size: 7.25″ L x 6.5″ W x 7.25″ H (18.4 cm x 16.5 cm x 18.4 cm)

Provenance: Ex Peter Arnovick Collection, Los Altos CA

Estimate: $700-$1,200

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

Tenenku Sculpture

Description : Africa, Tenenku culture, Mali, ca. 13th to 16th centuries CE. This is a seated terracotta humanoid figure on a slight platform; the figure has elongated facial features, bracelets and anklets. It appears to be female but may also be interpreted as having both male and female characteristics. The Tenenku people, part of the Malian Empire, are known for their powerful anthropomorphic and zoomorphic sculptures. The Islamic Malian Empire lasted for four hundred years; the emperors traced their ancestry back to Bilal, Mohammed’s muezzin, who was thought to have journeyed to the west and settled the area of modern day Mali. The empire had consistent contact with the rest of the Islamic world, and history records visits by emperors to Mecca. Interestingly to us, the Malian Empire often absorbed smaller cultures, like the Tenenku and their rough contemporaries the Bura, without changing their artistic styles — so a piece like this one was made around the same time as the completely different looking Bura grave markers! Unfortunately at this time we do not know the function of these large, heavy pieces of pottery — but hopefully with more research, we will soon find out!

Size: 12″ L x 9.2″ W x 18.75″ H (30.5 cm x 23.4 cm x 47.6 cm)

Provenance: Ex-Dr. Peter Arnovick Collection

Estimate: $1,200-$1,500

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

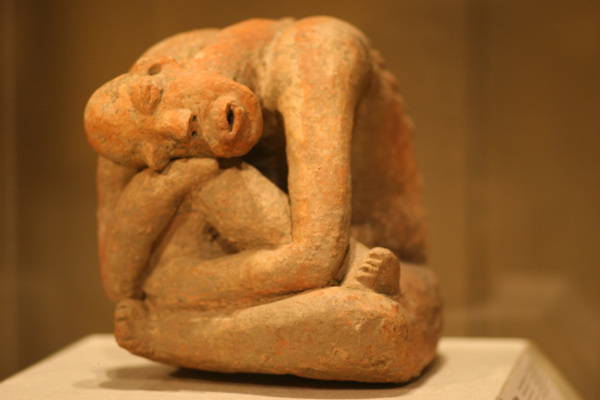

Sokoto Sculpture

Description : Sokoto, modern day Nigeria, ca. 500 BCE to 200 CE. This is a hollow terracotta shrine figure showing a full body, with the head larger proportionally than the rest and a cylindrical body; it is a male figure with arms and legs curled, wearing elaborately coiffed hair and a beard. Sokoto state in modern day northwest Nigeria is in the Niger River Valley, at the confluence of ancient trade routes and roughly contemporary with the Nok culture to its south. Very little is known of the ancient Sokoto culture; Bayard Rustin, who originally collected the Sokoto collection for the Yale University Art Gallery, recorded that most terracotta pieces like this one were found in large manmade mounds. Characteristic Sokoto figures are large, hollow, thin-walled, and low-fired human figures with heavy eyebrows and beards. They are made of a rough earthenware mixed with quartz and mica, surfaced with an ocher or mica schist slip (some of which has worn through on this figure). This slip would have been burnished with a smooth pebble.

Size: 5.75″ L x 8.75″ W x 20.2″ H (14.6 cm x 22.2 cm x 51.3 cm)

Provenance: Ex. Peter Arnovick Collection

Estimate: $800-$1,000

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

Koma Sculpture

Description : West Africa, North Ghana, Koma, ca. 16th century CE. A female pottery figure elaborately detailed with traits characteristic of the Koma figurines including an elongated head with large coffee-bean shaped eyes, as well as other bold features, especially a pronounced chin, and stylized coiffure. She is further adorned with an applied necklace/collar, loin cloth, armlets, and bracelets. Striking too are her extremely long fingers, pronounced breasts, and “outie” navel. Koma figures were first discovered in the 1980s during archaeological fieldwork directed by Professor Ben Kankpeyeng (University of Ghana). Created by a previously little-understood people in what is known as Koma Land, the figures are often fragmentary. This example, however, is in excellent condition. Although there is a paucity of literature on how such figurines were used, scholars have suggested they were used in special ceremonies and rituals in which the spirits of the ancestors were invoked. This piece has a concave receptacle atop her head, and it is possible that liquid offerings or libations were poured into it. Some have associated this practice with healing rituals.

Size: 3.25″ W x 12″ H (8.3 cm x 30.5 cm)

Provenance: Ex Peter Arnovick Collection, Los Altos CA

Estimate: $500-$700

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

Igbo Terracotta

Description : West Africa, Niger River Delta, Igbo, ca. late 19th to early 20th century CE. A fascinating terracotta shrine effigy created by the Igbo peoples of the Niger River Delta, its unusual form elaborately adorned at the top end with two human visages with bold coffee bean shaped eyes and scarification marks upon their foreheads beneath what appear to be two beak-like forms, the opening between holding an old wick. Across the body of the vessel are two magnificently modeled salamanders and cross-hatched designs perhaps representing additional scarification marks.

Size: 3.5″ W x 7.875″ H (8.9 cm x 20 cm)

Provenance: Ex Peter Arnovick Collection, Los Altos CA

Estimate: $400-$600

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

Bura Terracotta

Description : Africa, Bura /Asinda / Sikka area, present day Niger and Burkina Faso, ca. 1000 to 1500 CE. This is a thick-walled, smooth terracotta cylindrical figure with three nubbins representing sexual organs, a prominent nose, small mouth and eyes, and decorated hair. Unfortunately, little is known about the culture that lived in this area when this statue was made, because it was only recently discovered and there have been very few scientific excavations. What has been found are large cemeteries with impressive necropoli, which provide evidence that this was a wealthy, complex society. They buried their dead in conical urns, often topped with figures decorated with incised or stamped patterns like this one.

Size: 4.25″ L x 4.25″ W x 10.25″ H (10.8 cm x 10.8 cm x 26 cm)

Provenance: Ex-Dr. Peter Arnovick Collection, Los Altos, CA.

Estimate: $550-$650

Source : Artemis Gallery, 2015

Akan Head.

Description : Ca. mid 19th century, Akan Tribe, head of female, used and placed at the grave site, measures 10″ tall.

Estimate: $500-$700

Source : Estates Unlimited, 2005

![[E2] Djenne-map](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/djenne-map.jpg)

![[E3] Djenne terracotta - Metropolitan Museum of Art](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/met-jenne-03.jpg)

![[E4] Djenne terracotta - Metropolitan Museum of Art](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/met-jenne-02.jpg)