The Tussian, and Siemu tribes of Burkina Faso are small tribes which may share a common ancestry. Although they have developed cultural differences, they maintain a similar style in their representation of the buffalo helmets.

There’s no getting around it. The numerous times I saw photos of the helmets shown below I sort of missed the mark. Once understood however the symbology serves to enhance the appreciation of the art. Another aspect of this is the quiet symbiotic relationship (read as tolerance) the egret, and buffalo share. In collecting African Tribal art the development of the appreciation for pieces (learning curve) is a driving force/component for expanding one’s collection.

![[E1] Helmet Northern Tussian or Siemu, Burkina Faso](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ts-helmet-01w.jpg)

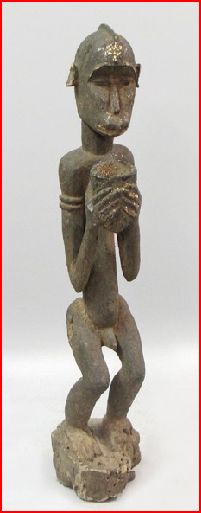

[E1] Helmet Northern Tussian or Siemu, Burkina Faso

The main horns at the sides are a no-brainer, but the “stylized representation of a buffalo with a pair of curving horns projecting from a flat, rectangular head, a tubular body standing on four legs, and a vertically projecting tail” totally eluded me. The upright figures between the buffalo’s horns, on the tail, or the rear near the tail represent egrets, oxpeckers, or both.

![[E2] Helmet - Northern Tussian or Siemu](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ts-helmet-02w.jpg)

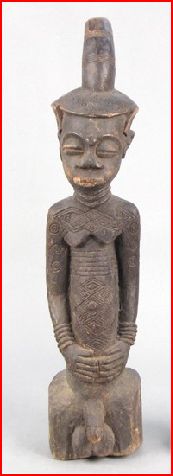

[E2] Helmet – Northern Tussian or Siemu

One notable difference with the helmet shown below is the absence of the two large curving horns which can be attached to the helmet with a fiber cord, or leather strips.

![[E3] Buffalo Helmet Mask (Kablé)](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ts-helmet-03w.jpg)

[E3] Buffalo Helmet Mask (Kablé)

Why the imagery, and representation of the buffalo?

“The buffalo holds special cultural significance in many parts of Africa. Life other powerful animals, such as the leopard, elephant, and ram, the buffalo is often associated with ideas of leadership and prestige. Allen Roberts (1955:22-25) has pointed out that both the animal’s behavior and it’s anatomy have captured people’s imagination. The fact that buffalo live in herds and cows usually bear a single young has led to an ideological linking of the animal with humans.”

[1] Buffalo Helmets of Tussian and Siemu Peoples of Burkina Faso. African Arts, Vol 41 #3, pg 26-43.

[E1] Afrika Museum, Berg en Dal, Netherlands

Photo credit : Ferry Herrebrugh, Amstelveen, Africa Museum

[E2] Acquired by Herta Haselberger in Bobo-Dioulasso (1967)

Photo credit : Sotheby’s Paris

[E3] Metmuseum

Buffalo Helmet Mask (Kablé)

Date: 19th–mid-20th century

Geography: Burkina Faso, Province du Kénédougou

Culture: northern Tussian or Siemu

Medium: Wood, cane, fiber ropes

Dimensions: H. 27 1/2 x W. 14 3/4 x D. 11 7/8in. (69.9 x 37.5 x 30.2cm)

Classification: Wood-Sculpture

Credit Line: The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979

Accession Number: 1979.206.47

![[E1] Helmet Northern Tussian or Siemu, Burkina Faso](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ts-helmet-01w.jpg)

![[E2] Helmet - Northern Tussian or Siemu](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ts-helmet-02w.jpg)

![[E3] Buffalo Helmet Mask (Kablé)](https://sm76626.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/ts-helmet-03w.jpg)